There are no more lions. It was the opposite.

It turns out that the team, which included researchers from the University of British Columbia, the McGill University, and the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Ont., discovered a previously unknown pattern that connects prey and predator species in ecosystems around the world.

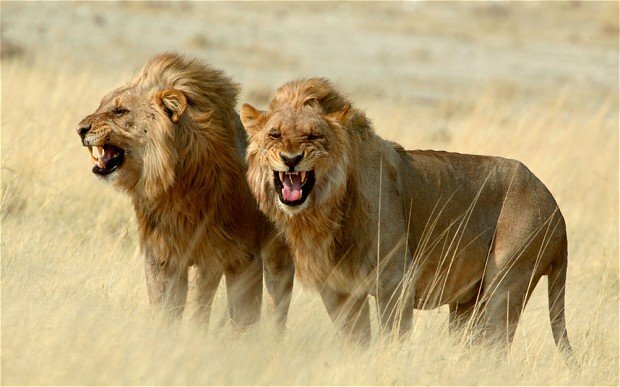

Even when there are plenty of prey around for larger creatures like lions to eat, the number of lions in an area does not increase, said the findings in the journal Science. They found that it’s not just lions and gazelles that are part of this particular pattern, but also other organisms that the team studied, such as plankton-eating crustaceans or bigger fish swimming in the ocean.

It came about by chance.

However, that was not the case; what happened each time was that productive grassland always resulted in a dramatic fall in the ratio of predators to prey. Thus the prey population is made up of many healthy adults. “This shrinkage is nearly as severe as rainforest loss”, he added. After beginning his PhD studies at McGill, he returned there to compare communities of African animals in protected ecosystems to investigate the relationship between carnivore numbers and available prey. When the scientists put the data together, though, they found an unexpected pattern: in every park, there seemed to be a consistent relationship to predator and prey in an unusual way.

“Until now, the assumption has been that when there is a lot more prey, you’d expect correspondingly more predators”, says Hatton. According to the new discovered law, more crowding leads to fewer offspring.

What makes the new study so impressive is the surprising consistency in the relation of predators to prey across all environments, and offers irrefutable proof that instead of the numbers of predators increasing to match available prey in an area, the populations of predators are actually limited by the growth rate of prey populations.

Over the course of the next few years they analyzed data gathered about both plants and animals from more than 1000 studies.

What the researchers also found intriguing was that the growth patterns they saw across whole ecosystems, where large numbers of prey seemed naturally to reproduce less, were very similar to the patterns of growth in individuals. During visits to multiple parks, a team, led by him found that the parks all had some nice treats for their lions which meant their population should automatically increase but what they found was completely different.

The research was funded by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).