The team, which identified the new technology, also had members from the same team, which first identified CRISPR-Cas9 system for mammalian genome editing. The bacteria in her samples were observed carrying out Cas9 proteins, which were able to cut the DNA based on an RNA guide sequence with great precision.

The application of the CRISPR-Cas9 system for mammalian genome editing was first reported in 2013, by Zhang and separately by George Church at Harvard. In the latest study, Feng Zhang and colleagues searched through bacterial genomes to find different versions of Cpf1. Though the system works perfectly for the objectiveof disabling genes, often times, it is hardto edit them through replacement of one DNA sequence with a different one. The cuts caused by the enzyme are healed by the natural process of DNA fixthat the cells have. Levi Garraway, who is from the Broad Institute but was not involved in the study, said that plans to harness the Cpf1 in cancer research are being made. Cpf1 enzymes from as many as 16 different bacteria were evaluated by scientists and they eventually found two that could be used to cut human DNA.

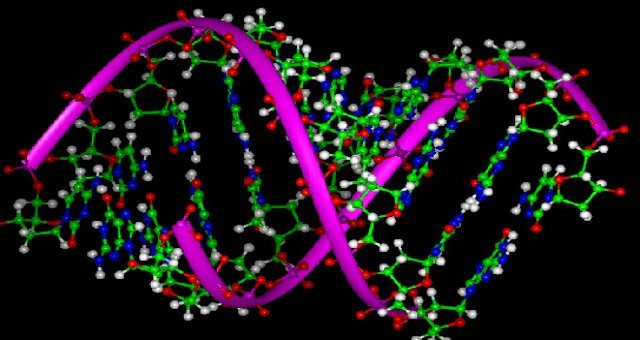

In its pure type, the DNA-chopping enzyme Cas9 varieties a posh with two small RNAs, each of that are required for the slicing exercise. The Cpf1 enzyme is much smaller than the previously used SpCas9 enzyme, which makes it much easier to deliver into cells and tissues. When Cas9 cuts DNA, it splits both strands of the molecule in at the same place, leaving blunt ends behind that are subject to mutations upon being reconnected.

With the Cpf1 complicated, the cuts within the two strands are offset, leaving brief overhangs on the uncovered ends. This is expected to help with precise insertion, allowing researchers to integrate a piece of DNA more efficiently and accurately.

Third, even if it results in a mutation, Cpf1’s ability to cut far away from the recognition site allows multiple opportunities for correct editing to occur.

The Cpf1 system provides new flexibility in choosing target sites. Like Cas9, the Cpf1 complex must first attach to a short sequence known as a PAM, and targets must be chosen that are adjacent to naturally occurring PAM sequences.

Cpf1, a protein that looks very different from Cas9, but is present in some bacteria with CRISPR, was also intriguing to the scientists. This could be an advantage in targeting some genomes, such as in the malaria parasite as well as in humans.

“This has dramatic potential to advance genetic engineering”, remarks Eric Lander, who is the Director of the Broad Institute as well as one of the principal leaders of the human genome project. “The Cpf1 system represents a new generation of genome editing technology”, he added.

The properties of Cpf1 that enable precise editing, opens the door to more applications, including cancer research.

The researchers have proposed to share the Cpf1 system worldwide through free academic research.

Zhang concludes: “Our goal is to develop tools that can accelerate research and eventually lead to new therapeutic applications”. “The greatest value may be more in terms of the patent landscape than a scientific advancement“, says Dan Voytas, a genome-editing researcher at the University of Minnesota.

The question on everyone’s minds now is – will this new enzyme surpass Cas9 in popularity?

Further the team was also puzzled by Cpf1, a protein whose appearance was distinct from Cas9 but seen in some bacteria with CRISPR.

In 2014, Zhang, along with the Broad Institute, won the patent for the CRISPR technology despite the fact that research from University of California, Berkeley predates their own.